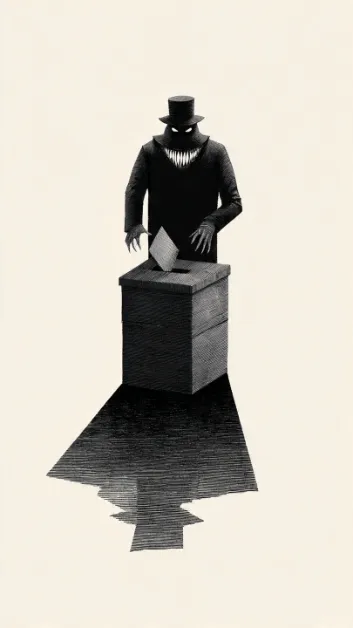

"We have 54,000 police officers; each has about 120 bullets. Do the Maths.”

Coercive Arithmetic, Electoral Sincerity, and the Rhetorical Displacement of Democratic Persuasion in Uganda.

21 Dec, 2025

Share

Save

1. Introduction

Electoral periods represent constitutionally sensitive moments in democratic systems, requiring heightened adherence to principles of popular sovereignty, political equality, and freedom of political participation. Political statements made by incumbents during such periods, therefore, carry normative weight beyond ordinary political speech. They shape public perceptions of whether elections constitute meaningful mechanisms of political change or merely procedural rituals.

This article analyses a statement attributed to the President of Uganda and reported in the Daily Monitor, in which he warned prospective protesters during the campaign period in the following terms:

“We have 54,000 police officers. Each one has about 120 bullets. Do the maths. Those who want to cause chaos will regret it.” (Daily Monitor, 2025)

The central argument advanced here is that, when examined philosophically and constitutionally, this statement does not function primarily as a neutral deterrence warning. Rather, it rhetorically displaces democratic persuasion with coercive capacity, raising serious questions about electoral sincerity, the meaningfulness of elections, and the implied relationship between popular will and political continuity.

Constitutional Framework: Popular Sovereignty and Electoral Meaning

Article 1(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda provides that all power belongs to the people, who shall exercise that power in accordance with the Constitution (Government of Uganda, 1995). Articles 20–29 guarantee fundamental rights essential to democratic participation, including freedom of expression, assembly, and association.

Ugandan constitutional jurisprudence has repeatedly emphasised that political rights are not ornamental but functional: they exist to ensure that citizens can influence political outcomes through lawful means. In Muwanga Kivumbi v Attorney General (2008), the Constitutional Court warned against executive conduct that, even without formal prohibition, produces a chilling effect on lawful political participation.

Against this backdrop, the rhetoric employed by political leaders during elections becomes constitutionally relevant. Language that undermines the perceived efficacy of elections indirectly erodes the constitutional promise of popular sovereignty.

“Do the Maths”: Rhetoric, Sincerity, and Discursive Choice

The phrase “do the maths” is not an incidental expression; it is a deliberate rhetorical device. It invites citizens to calculate political reality not in terms of votes, persuasion, or constitutional entitlement, but in terms of ammunition ratios.

In electoral contexts, sincerity is ordinarily demonstrated through rhetoric that affirms:

numerical support among voters,

confidence in electoral victory,

and respect for elections as decisive instruments of political change.

Conspicuously absent from the statement is any assertion that:

The ruling party commands majority support among the 45 million citizens, or electoral victory is assured through democratic persuasion.

Instead, the statement shifts immediately to coercive capacity. This omission is analytically significant. As political communication theory suggests, what is not said can be as revealing as what is said (Fairclough, 2013).

The rhetorical choice to emphasise bullets rather than ballots raises doubts about the sincerity with which elections are presented as determinative.

Counterfactual Democratic Rhetoric: What Confidence Would Sound Like

A counterfactual rhetorical analysis is instructive. A leader confident in popular support could plausibly have stated:

The majority of Ugandans support our party and our programme. We are confident of victory through the ballot. Even if a small minority attempts disorder, the security forces will protect democracy for all citizens, including those who support us.

Such a formulation would have:

grounded authority in popular numbers,

affirmed elections as the primary mechanism of change,

and positioned coercive force as secondary and protective.

The decision not to adopt such language suggests that electoral legitimacy was not the rhetorical priority. Instead, continuity of power was framed as independent of electoral arithmetic.

Coercive Arithmetic and the Reclassification of Citizens

By juxtaposing “54,000 police officers with bullets” against “45 million people”, the statement reclassifies citizens from rights-bearing political agents into security variables.

This produces three important discursive effects:

Depoliticisation of dissent

Political disagreement is often reframed as potential criminality or chaos, rather than a legitimate democratic expression.

Marginalisation of the numerical majority

Demographic superiority is rendered politically inconsequential in the face of armed capacity.

Normalisation of pre-emptive intimidation

Citizens are encouraged to internalise the futility of collective action before any action occurs.

This rhetorical move subtly, yet powerfully, communicates that elections may not meaningfully alter political outcomes.

Power, Violence, and Electoral Anxiety

Weber’s conception of the state as the monopolist of legitimate violence presupposes legitimacy derived from social acceptance (Weber, 1919). Arendt, however, distinguishes power—arising from collective consent—from violence, which emerges when power is threatened or weakened (Arendt, 1970).

In this theoretical light, the invocation of ammunition during an election period signals not confidence, but anxiety. Violence is rhetorically mobilised precisely because persuasion is uncertain.

The statement, therefore, operates as a compensatory assertion: it reassures political continuity not through votes, but through force.

Electoral Consequences: When Votes Are Rhetorically Neutralised

The most consequential effect of such rhetoric is not immediate repression but normative erosion. When citizens come to believe that elections cannot produce real change, democratic participation loses meaning.

Comparative scholarship shows that democracies often erode not through coups, but through gradual delegitimisation of electoral agency (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018). Rhetoric that foregrounds coercion over consent accelerates this process.

The Real Message, Analytically Decoded

Stripped of political caution, the statement communicates the following proposition:

Even if the majority does not support us, leadership will continue because coercive capacity overrides demographic numbers.

This proposition is fundamentally incompatible with Article 1 of the Ugandan Constitution and undermines elections as instruments of popular sovereignty.

Conclusion

The statement “We have 54,000 police officers… do the maths” is not merely a warning against disorder. It is a rhetorical redefinition of political reality. It shifts the foundation of authority from consent to capacity, implying that elections may not serve as effective mechanisms of substantive change.

In constitutional democracies, the language of leadership matters. When bullets are invoked where ballots should suffice, the promise of democracy remains formally intact but substantively hollowed.

The danger lies not only in what such statements threaten, but in what they teach citizens to believe about the limits of their political agency.

References

Arendt, H. (1970). On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Daily Monitor (2025) Museveni warns protesters: ‘We have 54,000 police officers… do the maths’. Kampala: Nation Media Group, December.

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

Government of Uganda (1995). The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda. Kampala: Government Printer.

Levitsky, S. and Ziblatt, D. (2018). How Democracies Die. New York: Crown Publishing.

Muwanga Kivumbi v Attorney General [2008] UGCC 5.

Weber, M. (1919). Politics as a Vocation. Munich: Duncker & Humblot.